Matter Bio: Learning from 400-Year-Old Sharks to Protect the Human Blueprint

Inside the largest-ever study of genomic stability and human longevity Based on an exclusive interview with Christopher Bradley, Founder and CEO of Matter Bio

A longevity study like no other

Matter Bio is launching what CEO Christopher Bradley calls “the largest study of its kind.” On the human side, the project will include up to 10,000 centenarians and 20,000 of their relatives, a cohort ten times larger than any ever assembled.

On the animal side, the study will cover dozens of long-lived and short-lived species, with around 30 individual animals per species. Each animal contributes nine different tissues, and each tissue is analyzed with three omics readouts, creating a dataset of unprecedented density and scale.

Crucially, the comparisons are not just between humans and animals. As Bradley explains: “We are not comparing sharks to people. We're comparing sharks that live 400 years to sharks that live 20, whales that live 200 years to whales that live 15, and then that difference we're comparing to us and to see what's going on.”

This design isolates the genetic and molecular factors that distinguish longevity even within the same species — a powerful way of teasing apart correlation from causation before extrapolating those mechanisms to human biology.

The goal is ambitious: to uncover the genetic and molecular machinery that keeps DNA stable in the longest-lived organisms on Earth — and then translate those strategies into therapies for humans.

Why DNA stability?

Bradley’s first-principles lens treats aging as information loss driven by damage and entropy. “I believe that time is kept in the DNA of the cell, the blueprint of the ship, of Theseus' ship. The blueprint… gets scratched, aged, changed, broken, rearranged. Then things start to go wrong. And that is not programmed. I think it's random.”

Damage, he argues, is inevitable—both endogenous and exogenous. “Life, humans and cells and all life on Earth is busy maintaining order despite the universe wanting to create disorder and destroy the order that exists.”

Within that frame, telomere attrition, epigenetic drift, and protein misfolding are all forms—or consequences—of information loss: “So I think telomere attrition is another form of information loss… If you solved telomere attrition, great. You wouldn't solve the loss of information in between those two ends.”

Comparative mutation work also shapes his view: across animals, end-of-life mutation burden clusters within a range, but the rate of accumulation tracks lifespan. “A mouse will get hundreds of mutations a year, and a human will get dozens… at the end of life, they'll both have 2,000 to 5,000 mutations per cell.” For Bradley, “we think it's because of damage. Damage leads to mutation.”

Beyond the hype: resetting vs. protecting

Epigenetic reprogramming is one of the hottest ideas in longevity science. The hope is that if aging is driven by “epigenetic drift,” then resetting the clock could restore youthful function and recover lost information.

Bradley doesn’t dismiss this. “I think you could reverse it. I think that's totally possible but I don't think it's easy.” He gravitates toward synthesis, not rivalry: “I like unified theories whenever I can get them.” In his framing, reprogramming and protection are not opposites but complementary — long-term rejuvenation may well require resets, but the tractable near-term lever is to reduce damage and improve repair.

The hesitation, he argues, is complexity. “Every single cell in your body has a role, has a stage, has a network of interactions… some of those interactions had to only happen in utero when you were a blastocyst.” In our conversation, he used the analogy that it takes nine months to “program” a human being — but importantly, development does not stop at birth. Puberty, experience, and daily environment keep layering epigenetic marks.

That raises a philosophical risk: partial reprogramming aims to rewind the clock without erasing cell identity — but even then, there are concerns. Epigenetic marks don’t only record age; they also capture development, experience, and adaptation. Resetting them on an organismal level could in theory rejuvenate tissues, but might also risk altering some of the very programming that makes us who we are.

As Bradley put it about the nervous system: “Your brain, you don't want to reset that completely, right? The structure there is important, epigenetically as well as larger scale.”

So he prioritizes an upstream, tractable lever: protecting and repairing the genome now, while more ambitious resets mature. “Antibiotics added 20 to 40 years of healthy life.”

He believes therapies that fortify DNA and enhance genomic stability could drastically extend human healthspan and help us reach the upper limits of our natural lifespan—buying time to develop whole-organism resets later.

Screening for DNA defenders

The study isn’t just observational; it feeds a pipeline of functional tests. Bradley describes their screen: “We're looking at what combinations can defend the cell against the largest different numbers of types of damage. UV, chemical damage, reactive oxygen damage.”

The combinatorics are huge. “Find a bunch of genes, combinations of those genes… there’s 500 top hits… the combinatorial number of those hits is astronomical. We're talking trillions and trillions of different combination potentials.”

Still, they’ve already found promising sets: “We have combinations already that are really good at defending the cell… you take a combination, you give it to the cell, and then you bombard those cells with damage and see how they stack up, the best combinations mitigate or outright negate the induced damage, which is similar to what we're seeing in long lived animals.”

The challenge of translation

Finding protective genes is one thing. Making them work in humans is another. Bradley is clear: “For all of our candidates, we do single gene screens first… But it’s tough, because, first of all, it’s probably not one gene, right? Because if it was, statistically you’d see at least one person who just doesn’t seem to die, living not a bit past 100 but much much past it. A methusalah. And as far as we know, we don’t see that, nobody has lived past 120, and even those upper limits are somewhat controversial..”

Combinations are usually required, and sometimes a gene that looks unhelpful on its own is actually a regulator that enables others. “So we have a single gene screen, but it's not as simple as just pick the ones that work best because sometimes you need a cocktail that has more thought put into it.”

Simply cranking up DNA repair proteins can also backfire. “If you just take the actual proteins of DNA repair, so base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, HDR, and you just jack those up… it’s not great for the cell. It can stop division. It could mess up development.”

This is why context matters. Genes that protect sharks or naked mole rats might not work the same way in humans. “There are a lot of genes that sharks have that you don't have and you don't want, right? ”

To avoid dead ends, Matter Bio tests all candidates directly in human cells. “Everything we're doing is in human cells right away. So if it doesn't work in a human cell, it's probably not relevant for this.”

Even something as fundamental as lifespan can be tricky to measure in long-lived animals. “Like, sure, you have a shark, but how old is the shark…? We have no idea… We did carbon dating. So it's not even accurate. They may be a lot older than that. These might be… 600 years old, for all we know.” That uncertainty makes it harder to match biology to lifespan with precision — and underlines why Matter Bio’s large-scale, systematic design is so important.

Still, Bradley is fascinated by the evolutionary question: “All animals have DNA. Did nature evolve a unified strategy for protecting DNA that allows some animals to live longer…? Or did sharks evolve better DNA repair because they're in a highly damaging environment and naked mole rats have a different form of strategy…?”

His intuition leans toward convergence. “Since cells have been around a long time, and they've been exposed to the same things, and DNA is a shared molecule across the tree of life, [my intuition is] that it's probably been figured out in a unified way, or in a very easy-to-adapt way. But I'll let you know when we figure it out. That's what we're working on finding out.”

Progeria: proof in fast forward

For validation, they’re turning to accelerated aging. “Humans that are bad at DNA stability, age faster. That's what progeria is. The progeroid syndromes that we know, accelerated aging syndromes, are all about integrity of DNA, either directly or indirectly. You know, lamin A for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria. It's not directly about DNA at first glance, but actually the nucleus gets weakened and that leads to problems with DNA stability.”

That convergence—accelerated aging tied to genomic instability, and long-lived species with bolstered safeguards—reinforces the strategy. “Long-lived humans,e.g. Super centanarians seem to have superior DNA stability… And when you look at long-lived animals, they have superior DNA repair, DNA stability, not just repair, because they also have copies of P53 in some cases, Rad51, so genes that kill the cell if there's too much damage faster so it doesn't become cancer.”

Early signals from their screens are strong. “We're seeing incredible results already. That's the big takeaway. We're finding massive amounts of protection with our combinations against large amounts of different damage… We're about to test that in progeroid syndromes, as well as the effects the combinations have on the longevity of the cells and then eventually the lab animals that get the validated combination candidates.”

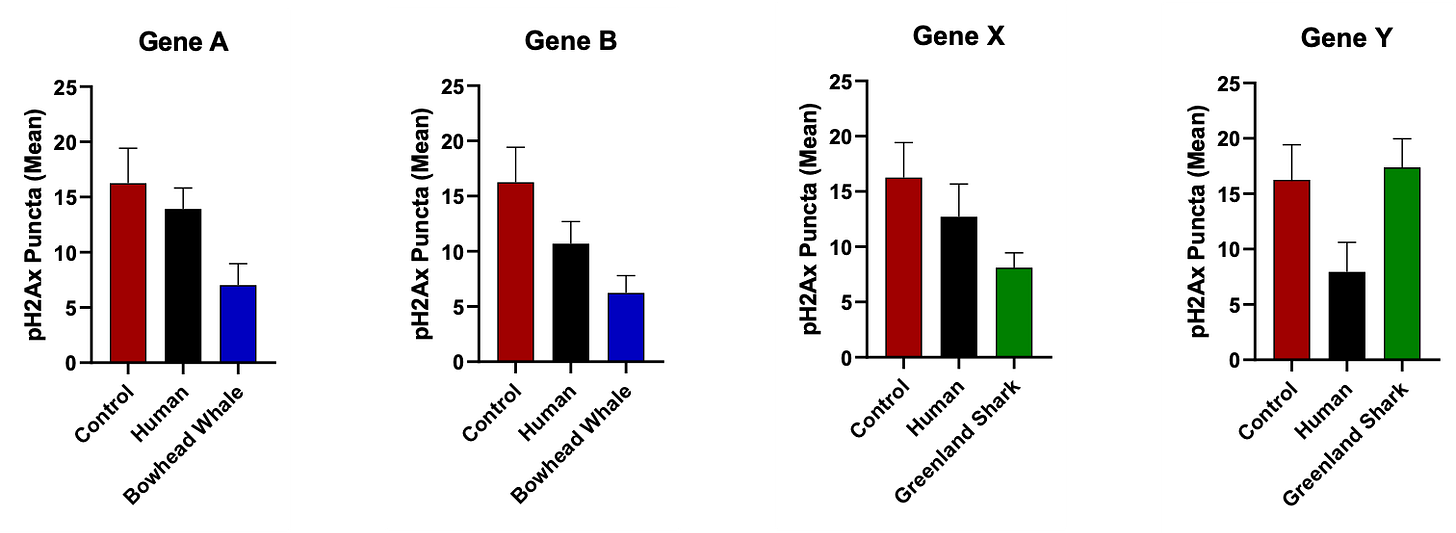

Figure 1. Each mini-chart shows how much DNA damage occurred when cells were given a specific “longevity gene” from either humans or a long-lived animal (such as a bowhead whale or Greenland shark). The height of the bars represents the number of DNA breaks (as measured by γH2AX-stained puncta, a standard marker of double-strand DNA damage).

In some cases, the animal version of a gene (blue or green bars) helped cells resist DNA damage better than the human version, but in others, it didn’t. This shows that every gene works differently depending on its context — the right mix, not just the species, determines protection.

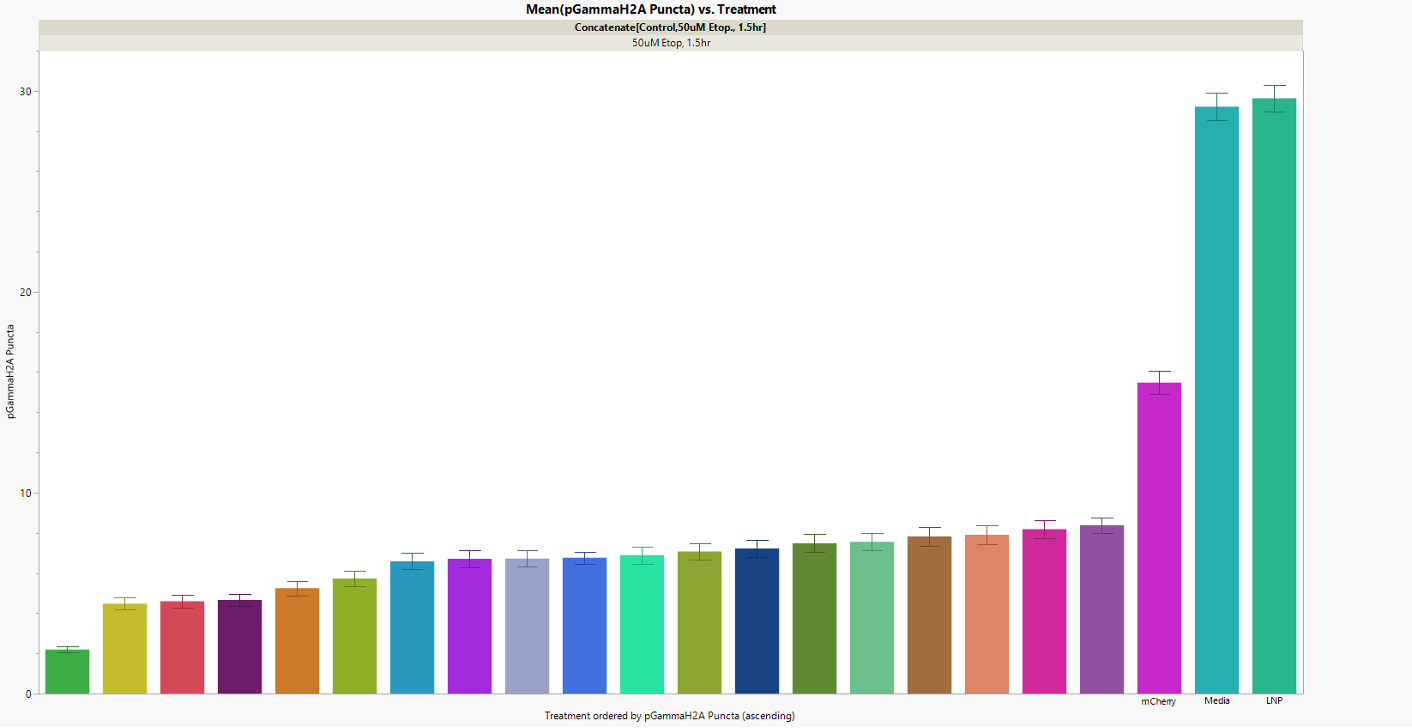

Figure 2. Each bar represents a different combination of protective genes tested in human cells exposed to a strong DNA-damaging chemical. The Y-axis shows the amount of DNA damage (quantified by γH2AX puncta counts) — so shorter bars mean stronger protection.

Several combinations shielded cells remarkably well. The best one reduced DNA breaks by about 87 %, leaving cells nearly as undamaged as the control cells that were never exposed to stress. In other words, these gene sets acted like a molecular armor against DNA damage.

The vision ahead

Bradley’s stance merges pragmatism with ambition. “Rejuvenation or reversing aging versus slowing it down are two different things… there's a lot of evidence in nature that you can slow it down a lot.” Give people the resilience nature already demonstrates: “Look at what's working for these animals and give it to people.”

And if we push the damage curve down, the societal payoff could be huge. “If our average lifespan is 150, I don't think a lot of people would complain.”

At its core, Matter Bio’s vision is simple but bold: to democratize longevity genes. Whether those protective variants come from supercentenarians or from animals that can live for centuries, the goal is the same — to transfer that resilience into everyone, not just the lucky few born with it.